Manicured wetland sucks up more carbon than natural marsh

Yingwuzhou Wetland, Jinshan District, Shanghai

A restored and carefully managed wetland on the Chinese coast is a much larger carbon sink than a natural marsh nearby.

Dr. Tang Jianwu at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) in Woods Hole (now at ECNU's IEC), Dr. Chen Xuechu at ECNU’s School of Ecological and Environmental Sciences in Shanghai and their colleagues measured the flows of three powerful greenhouse gases and found that wetlands restoration is crucial for both maintaining biodiversity and combating climate change.

Dr. Tang Jianwu

Dr. Chen Xuechu

The team found that the rehabilitated wetland took up more carbon dioxide and emitted much less methane than the natural one. As a result, the restored habitat has the net effect of soaking up twice as much carbon as the natural marsh.

Since 1970, 35% of the global wetland habitat has disappeared, largely owing to human activities. Over the past two decades, coastal wetlands in China have been enclosed by thousands of kilometers of seawalls to create extra land in support of the country's rapid economic growth. However, such a “new great wall” causes huge losses of ecosystem services and negatively impacts ecological security. In order to mitigate the coastal wetland losses, the Chinese government has launched a series of large-scale restoration projects along the coastal zone in recent years. Since 2009, Chen has worked as the leading scientist and main designer for some coastal restoration projects along the coastline of Shanghai. One of the projects he led was about Yingwuzhou Wetland, with an area of 23.3 hectare, located at the Citizen Beach, Jinshan District, Shanghai.

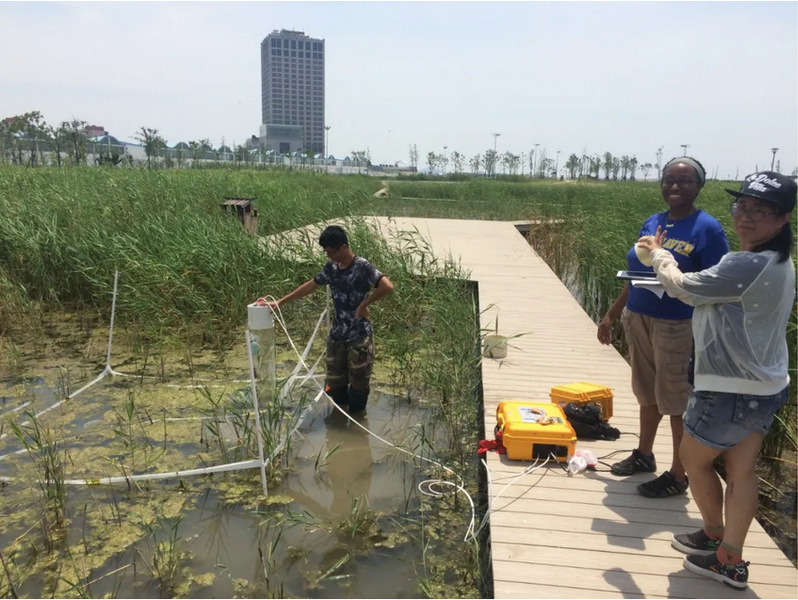

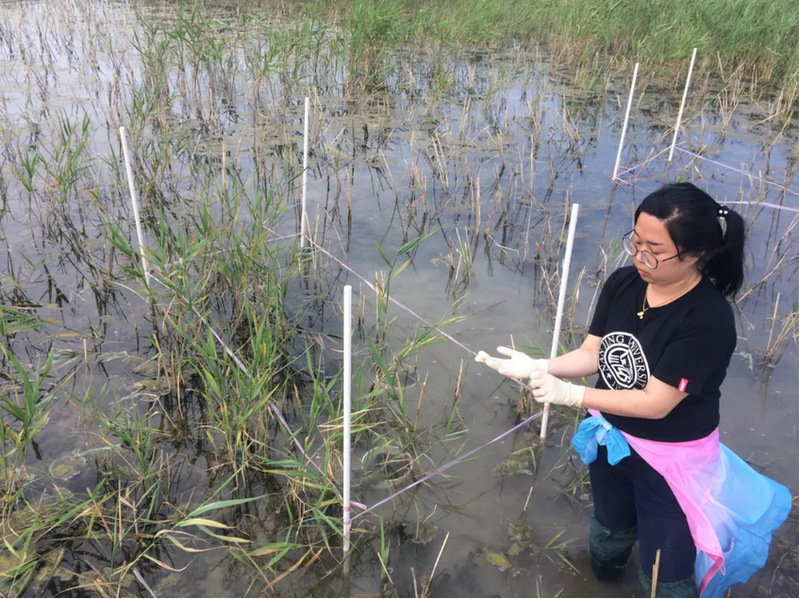

Members of the research team work at the Yingwuzhou Wetland.

Dr. Tang Jianwu is one of the world’s leading scientists in blue carbon studies, and he leads a global team including scientists from ECNU to explore the ecosystem value and mechanisms of blue carbon ecosystems worldwide. Chen worked at MBL as a visiting scientist in 2014 and 2015. After learning the methodology from Tang’s laboratory and returning to Shanghai, Chen became an associate professor of ECNU. In recent years, he has been trying to introduce the concept of blue carbon and incorporate it into coastal wetland restoration projects in China.

Since late 2017, Chen and Tang collaborated at Yingwuzhou Wetland to establish a novel coastal blue carbon assessment system and provide a scientific and technological basis for coastal wetland restoration activities in China. Dr. Hualei Yang, a postdoctoral fellow in their team, together with their students, measured GHG (CO2, CH4, and N2O) emissions to accurately estimate the blue carbon storage of the Yingwuzhou Wetland and the nearby natural wetlands.

Long-term field investigations revealed that water regulation and adequate plant biomass are emerging as an effective method to promote carbon storage in restored coastal habitats, which took up more carbon dioxide and emitted much less methane than the natural one. The success of Yingwuzhou Wetland demonstrates that similar approaches can be applied to wetland restoration projects in other geographical locations as a mechanism to maintain wetlands as carbon sinks and help mitigate GHG emissions.

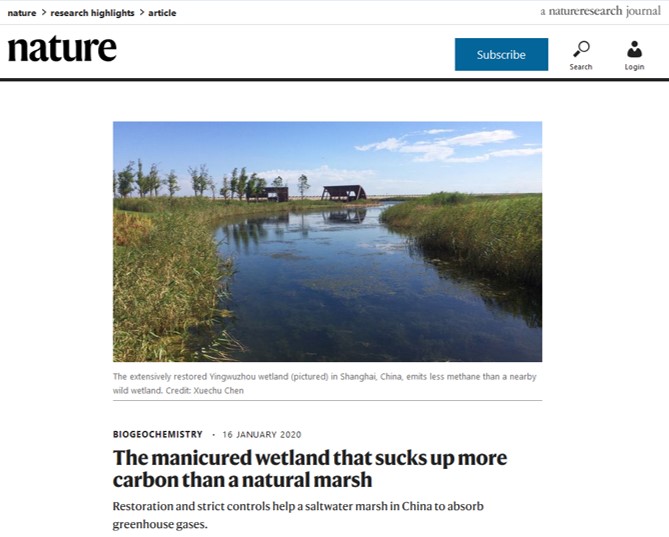

Nature highlights the research

The outcome of this study, titled “Enhanced carbon uptake and reduced methane emissions in a newly restored wetland”, was recently published in Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences. The pioneering research at the Yingwuzhou Wetland is attracting worldwide attention as it proves that wetlands restoration is crucial for both maintaining biodiversity and combating climate change. Nature highlighted this study on January 16, 2020, in an article titled “The manicured wetland that sucks up more carbon than a natural marsh”. This team is planning to expand their efforts and provides more nature-based solutions to fight global climate change.

Source: School of Ecological and Environmental Sciences

Copy editor: Philip Nash

Editor: Xu Xincheng